Posts Tagged ‘McGregor’

Where is Theory O?

[tweetmeme source=”strategic360s”]

I saw a commercial (Progressive?) recently where the theme is that some companies (their competitors) prevent their customer service personnel from providing optimal service, presumably by placing restrictions on what they can do. They use some great visual metaphors to communicate the message, including a receptionist in a glass box, a man in a large bird cage (suspended in midair), and this one:

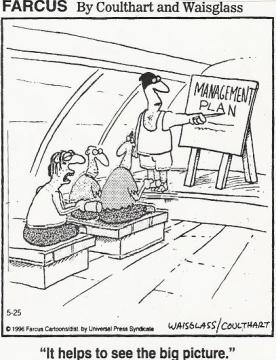

This picture of an employee in chains (who, evidently, can’t even get a cup of coffee, let alone serve his customers) also made me think of this cartoon that has a similar but nuanced message that just telling employees what they are supposed to be doing (i.e., alignment) isn’t enough if they are constrained.

(I am finding that some unknown percentage of viewers of this cartoon don’t “get” it, and I am wondering if it is, at least in part, due to lack of exposure to the slave rower (in the galley) in chains concept. It makes me think of the movie, Ben Hur, one of the greatest movies of all time, but one that many younger people (and most people are younger than me) have not seen. Am I right?)

The photo and the cartoon lead me to refer to the ALAMO© model that I use to help individuals, teams and organizations to diagnose why performance is sub-optimal:

Performance = ALignment X (Ability X Motivation X Opportunity)

I believe that the Opportunity part of this “equation” is one of the features that makes it somewhat unique, i.e., acknowledging that there are contextual factors that absolutely can constrain performance. The factors are also multiplicative so that the lack of any one feature drives the equation to zero (though Alignment can have a negative value).

Opportunity (or lack thereof) comes in many forms, both tangible and intangible. Hopefully employees aren’t physically chained or hung in bird cages, but the feeling can be as salient by policies and practices. Those can, in turn, come for organizationally communicated policies (e.g., policy manuals) as well as local (leader-determined) that may or may not be consistent with company strategies. Employees are also constrained tangibly by lack of resources, like the widget maker whose widget machine doesn’t work. Resources also include time, budget, information and support.

Opportunity constraints can also be psychological. They come in the form of norms, both company and local, regarding “how we do it around here.” They also can be internal, self-limiting thoughts or beliefs such as, “I don’t think they want me to do that,” and/or “I don’t think I can do that,” and/or not exploring sufficient options about how to get past barriers (which also may be perceived or real).

I had the opportunity to attend a presentation by Bill Treasurer earlier this year. His message focuses on another “O” leadership factor, namely to create opportunities by “opening doors” for others. His book is Leaders Open Doors, and he tells this little story in there and in his presentation:

When my five-year-old son, Ian, returned home from school, the youngster said his teacher had chosen him as that day’s class leader.

“What did you do as class leader?” I asked.

“I got to open doors for people,” said Ian.

This other “O” is a proactive form of leadership, which is creating opportunities for others. Let your mind wrestle with this metaphor. How do leaders open doors? A “door” might be an obstructive policy. It could be the door to access another person, maybe to get information, build relationships, or be a mentor. It could just be opening their own door. It may be creating options for a subordinate’s career development that require resources that the leader can control.

Whether the “O” is “opening doors” or ensuring “opportunity” to perform, the manager has the “keys to the kingdom,” which include access to resources and overcoming barriers. The best managers I had in my career were ones who helped me spread my wings by breaking down the cages.

This is such an important role for a manager that it is ludicrous to have 360 Feedback processes that do not involve the immediate supervisor and prevent their access to the report. Asking the participant to provide a “summary” instead of the report is fraught with significant perils, including real and perceived inconsistency (insert “unfairness” here).

Lack of “opportunity” can occur at all levels: organization, team, manager, and self. Here are some thoughts about how to improve it using various assessment tools:

- Use employee surveys with a dimension relating to Opportunity to Perform

- I have the resources to do my job well (equipment, budget, work environment)

- I get the information I need to do my job well

- The Policies and Practices here allow me to provide optimal customer service

- Use 360 Feedback/Upward Feedback to assess/improve manager performance in this area, and hold them accountable for improvement

- My manager regularly asks me if I have the resources I need to perform my job

- My manager helps our team to identify barriers to successful performance

- My manager discusses my short and long term career plans, and helps me progress with my development plan

- Define, train and assess to create coaching skills in all managers.

In my last blog, I asked the question, “Where is Theory Y?” (https://dwbracken.wordpress.com/2014/12/17/where-is-theory-y/) in response to an article that proposes that all that matters for effective leadership is achieving the goal, not how he/she got there. That led me to a reference to McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y, and the leader effectiveness factors of task and relationship. Today I propose a “Theory O” that is equally important to effectiveness as a leader (to deliver it as a manager), and as a job performer by staying aware of the real, perceived and imagined barriers to your own effectiveness.

©2014 David W. Bracken

Where is Theory Y?

[tweetmeme source=”strategic360s”]

This column in Forbes by Rob Asghar literally paralyzed me for a few moments.

Forbes is known for taking provocative positions at times but this one challenges some of my core values as to what it means to be a successful leader, let alone good person. In a nutshell, he argues that the only important factor in evaluating leader success is bottom line results, regardless of the process. In other words, any means to an end (thank you, Machiavelli). Rob has no data to support his position, but he protects himself by saying that successful leaders (and he, himself) do not care to hear from the “experts,” i.e., social scientists like many of us, about process. So what follows is probably an exercise in futility if I think it will ever be read by people like him. But it gives me the opportunity to bring to you a few nuggets that I’ve seen relating to this topic in the last few weeks. And a couple that go way back.

First, this discussion gives us the opportunity to acknowledge the 50th anniversary of Blake and Mouton’s seminal book, The Managerial Grid. (As an aside, dozens of people entered into a recent LinkedIn discussion I began in the I/O Practitioners space regarding what are some core knowledge areas an I/O Psychologist should be expected to possess, though the discussion went off in other directions. At one point I offered up the Hawthorne Studies, and I would add The Managerial Grid to that list. I will also add Douglas McGregor’s Theory X/Theory Y, discussed below.)

For the uninitiated, the Managerial Grid is a 9×9 matrix that plots leader behaviors on an X-axis (Task orientation) and a Y-axis (Relationship orientation). Not by coincidence, McGregor’s Theory X behavior is very task oriented while Theory Y describes a much more participative style (with McGregor being first, around 1960). In the Grid, ideal leader is 9-9, an equally strong emphasis on task and relationship. (I recall once when a colleague was trying to force me to do something and accusing him of trying to “9-1” me, that is to do something regardless of how I felt about it, which, by the way, is basically what Asghar is promoting.)

Leaders who demonstrate no respect for others occasionally do succeed. Of course, Steve Jobs is the most cited example. This past week I watch a PBS biography on Admiral Hyman Rickover, the father of the nuclear Navy, and I (and others) would add him to this list. He was universally labeled an “SOB.” No one could remember him ever saying “thank you.” But he was an obsessive believer in accountability, for both others and himself. And he was consistent. And, ultimately, he was successful in achieving his vision. Mr. Asghar also uses Nick Saban, very successful coach at Alabama, as another example. But these are extraordinary people and exceptions in many ways.

Here’s another article, this time from HBR, which not only has data, it is titled “The Hard Data on Being a Nice Boss.” https://hbr.org/2014/11/the-hard-data-on-being-a-nice-boss

Using various studies, the author (Emma Seppala) asserts the following:

- Putting pressure on subordinates that increases stress that leads to high health care and turnover costs.

- Acts of altruism increase status in the organization.

- Fair treatment leads to higher productivity and citizenship behaviors

- Leaders who project warmth are more effective.

- Employees that feel greater trust for a leader that is kind.

So there is a cost to being a Theory X (9-1) manager, i.e., the health and well-being of your employees. And the cost is getting bigger everyday unfortunately with the state of our healthcare system.

In my last blog (https://dwbracken.wordpress.com/2014/11/13/trust-again/), I revisited the concept of “trust” and labeled it the “sine qua non” (without which there is nothing) of effective leadership. Trust is a complex behavioral construct, but I totally agree that kindness is an important component. Kindness doesn’t have to mean being soft; it is more akin to empathy, having sensitivity to the feelings of others, particularly when the message is difficult. We are seeing “kindness” being mentioned in a growing number of organizations. Part of that comes from respecting the whole person and his/her point of view and emotions without having to abdicate the responsibility for delivering on individual, team and organization performance commitments.

This piece by Stephanie Vozza from Fast Company (http://www.fastcompany.com/3038919/mentor-or-best-friend-which-management-style-is-best) starts right off with this statement: “For decades, managers led with a heavy hand from corner offices.” She goes on to contrast that with how managers will be most effective in today’s workplace, building upon some work by the Addison Group. She (and they) maintains that the answer isn’t to be the “best friend” of subordinates, but instead to be a mentor who provides guidance and advice, both on daily performance and careers.

(I do disagree with 2 of her points. First, she maintains that this situation is being caused by the arrival of millennials that have different expectations of management. Au contraire! ALL workers have a need to be respected with all the leadership behaviors that that implies, including honoring the value and needs of each person.

Secondly, I take issue with the use of the word “mentor” in this context. We should clearly differentiate between “mentor” and “coach,” specifically manager as coach. But these points get us off track from our theme here.)

Having done employee surveys for over 35 years and 360’s almost as long, recurring themes in drivers of engagement and evaluations of leader effectiveness continue to be trust and support in helping employees develop and plan for careers.

Let me add one other point to the value of believing that the “means” is as important as the end. An I/O colleague told me of a piece of research that has stuck with him that indicated that a strongest predictor of employee ethical behavior was immediate manager ethical (or not) behavior. There are many potential explanations for why that is, but those are not as important as saying if we believe ethical behavior is important in our organization, we can observe and measure it, and, if it leads to more of that desired behavior, the organization and its customers will benefit. This, of course, applies to other important leadership behaviors, often captured in Values statements that hang on walls and too infrequently actually measured.

Allan Church and I bring the “how” versus “what” of performance into the Performance Management discussion in our article from last year (http://www.orgvitality.com/articles/HRPSBrackenChurch OV.pdf). One of the points we make is that organizations are very good at measuring the “what” side of performance (i.e., tangible, objective achievements) and much less adept at measuring the “how” (i.e., the means to the end, the behaviors demonstrated). A parallel argument can be made that leaders/managers/supervisors find it much easier to manage the “what” side, and, because it is more difficult, give much less (if any) attention to the relationship part of leading, including coaching.

We are certainly not advocating the abandonment of the “what” measures. We are suggesting that an overemphasis on the “how” side of leader behavior is needed until they balance out, both at the individual and organizational level, i.e., achieving more “9-9” management at all levels.

I suspect that the majority of the readers of this blog are the “experts” Asghar references and dismisses. And to you colleagues, I am hopefully preaching to the choir (as they say). If that is not the case, then please let us know what that position is.

For those of you not in the “choir,” I hope you read Asghar’s piece and see if you think he has a valid point. Reflect on both how it applies in your organization and for your own behavior as a leader/manager.

Everybody should sit back and reflect on where/when we see or don’t see Theory Y behavior at all levels of leadership and how to create more 9-9 leaders. We should demand accountability for both “what” and “how” measurement aligned with both strategy and organizational values.

©2014 David W. Bracken